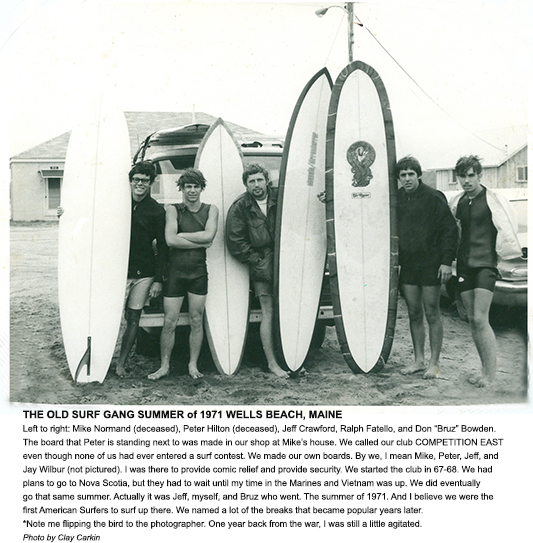

A DAY AT THE BEACH IN FLORIDA.

by Sam George

Only breaking even, but it was enough.

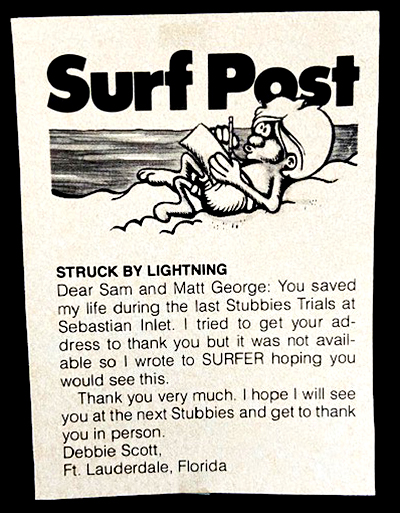

Florida is a crazy place. At least it seemed that way to us, my brother Matt and me, when back in 1983 we found ourselves in the Sunshine State, and more specifically at Sebastian Inlet, Florida’s premier surf break and site of the Stubbies East Coast Pro Trials. Located 14 hot, flat, cicada-buzzing miles south of Melbourne Beach, “The Inlet”, as it is known to East Coast surfers, is just that: one of only a handful of inlets along the low, sandy barrier island that stretches from the Canaveral National Seashore in the north to Port St. Lucie in the south, where the Indian River’s brackish water flows into the Atlantic.

This inlet is special, however, being man-made (first attempts to open a “cut” were recorded in 1905) and eventually man-improved over the ensuing decades, the most significant upgrade, so far as this story is concerned, occurring in 1970 when engineers, with absolutely no interest in the outcome other than keeping the inlet mouth from shoaling, finished work on a 500-ft. extension of the inlet’s north jetty.

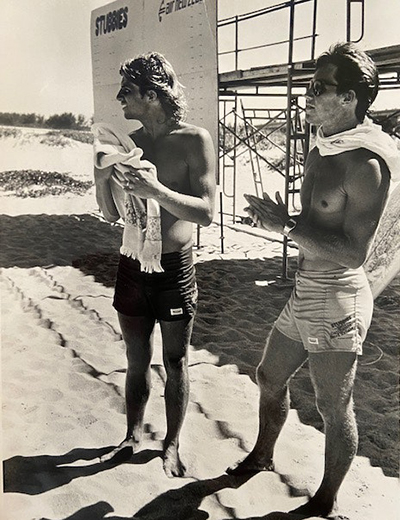

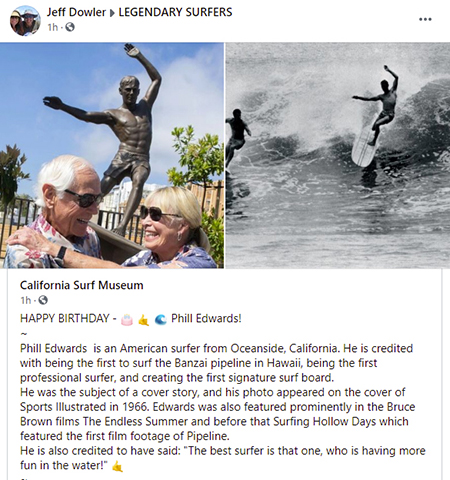

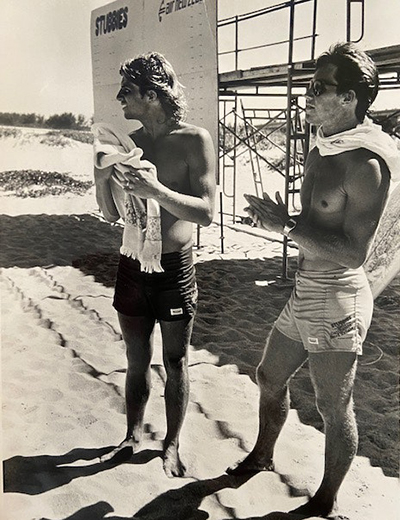

Above: Sam and Matt George at The Inlet in Florida in 1983.

The unintentional consequence being the creation of a near-shore refraction pattern that saw normally tepid Florida wind swell bounce off the new section of jetty and back into itself, forming a steep, hollow, wedge-like wave that very quickly became the East Coast’s most famous surf spot. While delighted Floridian surfers rejoiced, Floridian fishermen, good ‘ol boys all and heretofore the Inlet’s only local denizens, responded by casting epithets and lead sinkers at surfers floating next to the new jetty, convinced that, while these longhaired interlopers were most probably smoking pot and burning American flags, they were most certainly spooking all the snook, pompano, speckled trout. The history of this teacup range war, however, isn’t central to this account, its purpose simply being to establish that at Sebastian Inlet, and in Florida in general, there’s a lot of ways for a surfer to get hurt.

The surfer/fisherman feud was still raging when we got there in 1983, “we” being the Stubbies Pro Trials juggernaut, a series of regional events that provided competitive surfers from the West Coast, East Coast and Hawaii the opportunity to qualify for the Stubbies Pro, at that time one of the most prestigious competitive events on the international pro surfing circuit.

Held at Queensland, Australia’s fabled Burleigh Heads, “The Stubbies”, with its mainstream media coverage, man-on-man heats, huge crowds of spectators, tiny bikinis and gigantic cans of Castlemaine XXXX lager, was the sort of competitive spectacle that professional surf contests today can only dream of equaling. Every contest surfer in America wanted to join the top-ranked pros at The Stubbies, and unlike any other sponsor in the surf biz, the company gave them their shot with these regional events.

Couple things about Stubbies. The Aussie clothing company, founded in 1972, captured a considerable share of the market with a tough, very short short (named after a particularly stubby bottle of local beer) that became ubiquitous work wear for the country’s construction workers, known Down Under as “brickies.” In short, Stubbies were as “dinky-die” as you could get. Strange, then, that the first two surfers the company decided to sponsor, following its inevitable push into the burgeoning surf wear market, were Sam and Matt George, two small-time amateur competitors with big dreams who, when they weren’t working in a Santa Barbara surf shop, were moonlighting at a nearby trading post selling Levis, just trying to save up enough scratch to get to Hawaii for the winter season.

But sponsor us they did, finding us personable, earnest, reasonably attractive in ads and, given our natural gregariousness, good ambassadors for the brand. Which is why one sunny day we found ourselves driving down the A1A from the Melbourne Beach Holiday Inn to Sebastian Inlet every morning to hang out at the Stubbies East Coast Trials and be ambassadors. This included everything from talking to local TV reporters to occasional live commentary to recruiting Floridian beach girls—a very different species than those found in California, who can only “lay out” for a couple months in summer—for the always-popular bikini contest.

A task that proved as tricky for us as did the predictably tiny surf to the competitors. In fact, it was only afterward that the numerous “fuck off, pervs” made sense, when it was explained to me by a formidably endowed entrant how during last year’s event the contest organizers removed some of the cross braces from beneath the scaffolding’s plywood catwalk, so that when a contestant tottered out in her high heels and Brazilian bikini the all-male judging panel’s lusty stomping would cause the courageous girl’s marginally tethered breasts to heave up and down as if on a choppy sea. All in good fun, so they said, but I had wished they’d warned me before I started strolling up and down the beach with an awkward smile and a clipboard.

It was a crazy scene, what with the frothing surfers, die-hard contest fans, curious onlookers, brave bikini girls, surly fishermen, hot sun, even hotter parking lot pavement, only slightly less blazing sand, voracious horse flies and occasional pack of spinner sharks. Not exactly a relaxing day at the beach, but judging by the festive mood of the crowd, just another day at the beach in Florida.

Which is probably why nobody paid much attention when the sky on the eastern horizon took on a gray cast, like a smudged pencil streak across the broader expanse of blue. The smudge quickly morphed into a squadron of dark-bellied cumulus clouds that appeared to be slowly moving in our direction. Again, apparently no cause for concern, let alone alarm, for the beachgoers and contest crowd. Just another day at the beach in Florida.

We saw the first bolts of lightning long before the sound of distant thunder reached us, bright flashes stitching clouds to sea in a jagged, fiery seam.

Still no visible signs of concern from the beach at Sebastian Inlet. Not yet.

But as I sat in a metal chair under the shade of the contest scaffolding, reveling in the cooling onshore breeze that seemed to precede the approaching cloud galleons, I noticed fishermen on the jetty reeling in their baited hooks, packing up their tackle, and hustling back toward parking lot. None that I saw yelled anything to the pack of recreational surfers who, taking advantage of a break in the contest action, had packed the lineup.

The fishermen just grabbed their gear and split. Next on the move were the parents on the sand with small children, who with practiced aplomb rounded up their Coppertone-ed brood, stuffed sandy towels into beach bags and herded everyone up to the state park bath house, there to set up a new camp under its awning.

It was only then that I noticed how much louder the peals of thunder had become. And weird, because the ominous cloud bank appeared to be a long way off—the Inlet had lost its hot light, suddenly diffused, as if during an eclipse, but the clouds were still distant. I remember thinking…and then the earth seemed to stop spinning as a huge bolt of lightning struck somewhere near the end of the jetty, followed a frozen heartbeat later by the loudest, most terrifying, existence-shattering crack of thunder I’d ever experienced.

Then the heavens opened up and rained hell down on the Stubbies East Coast Pro Trials. My first thought was to get the hell out from under the aluminum scaffolding, so I got up and ran down the beach, being passed from the opposite direction by most of the surfers who were fleeing the lineup for the safety of the state park bath house.

Too many of the beach crowd, however, crammed themselves under the scaffolding, an imprudent course of action, I thought, with lightning striking all around. Meanwhile, Matt, stuck in the scaffolding scrum, was squirming through the tightly packed bodies in an attempt to join me where I lay flat on the sand, doing my very best to be the lowest object in sight.

The lightning no longer came as bolts, but merely sheets of white-hot light followed by the all-encompassing thunder. I cowered, eyes closed, fists clenched over my ears. During one short respite I looked up and saw two surfers—a guy and girl—still sitting on their boards, as if calmly waiting for a set. But before the sight completely registered I was blinded by another enormous strike and thunder combo that had me burying my face in the sand.

My ears rang—I had to shake my head to clear them.

When I finally did I heard Matt yelling my name from under the scaffolding. I looked back to see him pointing toward the water, gesturing wildly. I turned back to the lineup, saw nothing. Nothing. Matt kept screaming my name. Not in fear, but with urgent alarm. Another blinding crack of lighting, the smell of ozone strong. I cleared my vision, looked again—nothing. Nothing but two surfboards floating placidly, side-by-side. With nobody on them.

With nobody on them.

I jumped to my feet and ran toward the water.

With lightning striking almost nonstop now, I churned a serpentine course across the sand and down to the water’s edge, weaving as if I were dodging thunderbolts hurled down by some malevolent god and my zig-zags somehow made me harder to hit. But I got to the shore break unscathed, high-stepping it across the inside sandbar, then porpoise-ing through the oncoming rows of whitewater and out to where I last saw the surfers. The water was surprisingly clear, the surface smooth; it had started to rain. Once outside the surf line, I dove and dove, eyes open.

And this is when the fear gripped me.

Not fear of the lightning, or of danger, or even of failure; not honorable fear. But shameful, unmanning fear. Because with each plunge I knew that I might find someone who’d been hit by lightning. Hit by lightning. Wondering what that might look like; knowing that, despite the fact that I was treading water right here, maybe within a few feet of them, I didn’t really want to find out.

Just like that time before.

It was seven years earlier, and myself, Matt, Central Coast Surfboards owner Mike Chaney and our shop grom Bob Sennett were rolling south from San Luis Obispo on U.S. 101, our funky ski boat towing behind Chaney’s 1970 Torino. We were headed to the Gaviota Pier, gateway to The Ranch, that fabled stretch of private coastline west of Santa Barbara where all Californian surfer’s dreams come true. It was early—gas station breakfast early—and Matt and Bob were asleep in the Torino’s spacious back seat, Cheney behind the wheel, me vibrating with anticipation next to him. We’d passed Los Alamos a few miles back, the flickering “No Vacancy” sign at the town’s only motel winking at us like a red eye in the pre-dawn half-light.

The highway gently rises south of Los Alamos and we followed its undulating course through rolling hills peppered with craggy dark oaks. Then motoring around a corner we suddenly saw the bright red and orange flash of an explosion, its fiery epicenter across the grassy median on the northbound lane of the 101. No sound, for some reason, just an explosion, as if the world had, for a crystal moment, been put on mute. The flames and white smoke so incongruent on this quiet morning; in this quiet hour. Then we saw the car in the center of the flames, a blue Mustang, its front end crumpled against the gnarled trunk of a roadside oak tree.

Cheney pulled over and I got out of the car.

“Stay here,” I told Matt and Bob, roused now by the cessation of road song. The silence outside the car was eerie, not a sound but the crackling of the flames. I remember thinking, “Shouldn’t a crash scene be louder?” I ran across the median and stood as close as I could to the burning car, next to a man who had pulled over on this side of the highway. We both regarded the burning Mustang, acrid black tire smoke beginning to billow.

“If there’s anyone in that car,” he said, matter-of-factly. “There’s nothing we can do for them.” I nodded. He was right, of course.

“Hey, there’s someone over here!” This from a second man, who had exited the first man’s vehicle and now stood by the side of the road some 15 feet away, staring down at something in the grass. I ran over and saw that he was looking down at a body. Female by the look of her hair, raven’s wing black and cropped straight across at the nape of the neck. She was lying face down in the dry grass, with whatever she had been wearing as a top smoldering, the backs of her arms charred black to the wrists. Both legs had been severed mid-thigh. Had she dragged herself here, or been thrown?

The men stared; I counted. Because I stared, too, knowing what I should do, but not wanting to do it. Not wanting to gently turn that woman over and see her gruesome, charred, blackened face looking up at me while I tied off tourniquets and checked for a pulse. Hesitating, pulling back, afraid to act.

Afraid to see. So I counted: 10, 11, 12…16, 17, 18…”

Counting the seconds of life left with both femoral arteries cut. If she had been alive when thrown from the wreck, she couldn’t be now, I told myself, not at 20, 21…then Cheney was there, holding a beach towel. “What is it?” he asked. In the distance, the plaintive wail of an ambulance. I took the towel, covered the woman with it, and walked back to the Torino.

“What was it?” Bob asked. “A dead woman,” I said.

None of us spoke again until almost Gaviota. Then we went surfing. I can’t remember what the waves were like that day.

Now here I was again, in the rain and the lightning and thunder, coming up for air between dives, hoping my bobbing head was no tempting target, then back down, much more than half-hoping that I wouldn’t find either of them; that I wouldn’t have to see what the impact of 300 million volts on a human body looked like. Hesitating, pulling back again, in six feet of water off Sebastian Inlet in Florida, but right back on the side of the highway south of Los Alamos.

Then I saw her, the girl.

She was resting on the sandy bottom, half on her side, slender ankles crossed, long, dark hair waving gently in the current. The sky above was still crackling with deadly, latent energy, but here, below, about five feet down and swaying in the surge, she looked almost peaceful.

Muffled thunder rolled overhead; seconds ticked away. There she was. I stuck my head up, snatched a hurried breath, swam down, took her by the shoulders and pushed off for the surface.

Matt was here—he’d made his own mad dash across the beach and with another surfer named Scott Thomas was working a search pattern off to my right; diving, a quick breath, then diving. When I surfaced, struggling to keep the young girl’s head above water as a set of waves rolled over us, he quickly swam over and together we supported her body, face up, me at the shoulders, Matt at the knees.

“Neck broken maybe,” I yelled. “Try to keep her level.”

More lightning and thunder; short-interval waves battered us as we made our way toward shore, chest deep but with toes scraping the bottom for purchase. My right hand caught on a rough patch, like burnt skin, between her shoulder blades, but aside from that she was slippery, and hard to hold. Each successive wave threatened to loosen our grip.

“Wait, wait, I can feel the other guy with my foot,” yelled Matt.

“I got my foot on him.” Another wave washed over us.

“Can you drag him?” I yelled back.

“Not without letting go,” he said, sputtering salt water.

It was all we could do to hang onto the girl.

“Leave him,” I said, and we staggered on, fighting our way through the shore break, bearing her limp body up above the tide line.

By now a few others had joined the search, braving the now-diminishing lightning strikes to plough the surf zone, and Matt pointed to where he had felt the other body. I knelt next to the girl. It was too sandy and too crazy to feel for a pulse, but she had been down for three, maybe three-and-a-half minutes, at least, so I started CPR. A couple quick breaths, then trying to remember my camp counselor first aid training I began compressions. I’d barely reached three when she suddenly spewed up a gobbet of salt water and foam, coughed, then opened her eyes. Matt and I gently turned her on side, making sure her airway was clear, then carefully laid her back down.

“What happened?” she said in a loud voice. “What’s that noise?”

We were between thunderclaps, so I figured she must’ve burst her eardrums.

I didn’t want to scare her, but thought she should know.

“You were hit by lightning,” I told her.

“You may have ruptured your eardrums. But you’re alive. And you’re breathing.” Then Matt and I leaned over, trying to shield her from the rain, afraid to move her because who knew about the neck and spine.

She took my hand in hers.

“Don’t let go,” she said.

“I won’t,” I said. “We’re right here.”

So Matt and I covered her with our bodies as the rain beat down and the second surfer was eventually dragged up the beach and laid next to us. Pete Hodgson, an eminently capable local surfer/lifeguard, began CPR, the effort heroic, if nothing else, considering how long the kid had been down.

The girl never let go of my hand.

Not when the lighting and thunder eventually moved off to terrorize some other landscape, not when the clouds followed and the sun came back out, not even when the paramedics arrived, efficiently placing her on a red spineboard with a head mobilizer and carrying her across the sand and the steaming parking lot to a waiting ambulance. There I finally peeled her hand from mine, placing it carefully by her side, then leaned down to tell her that it was alright, that she was going to be okay. She couldn’t turn her head to look at me, so I’ll never know if she said anything in return. The ambulance hit the lights and siren and pulled away, a second ambulance in train.

The moms with their little kids had already headed back onto the beach, dry towels and sunscreen at the ready. The savvy fishermen on the jetty unlimbered spinning rods, eager to get their lines back in the water. The contest’s judges climbed back onto the scaffolding, a handheld air horn squawked. Over the scratchy loudspeakers: “Quarterfinal heat number one, please check in with the beach marshal.”

Just like that. Another day at the beach in Florida.

I stood there on the hot asphalt. Matt came and stood next to me. Neither of us could find anything to say. But I can remember what I was thinking. I was thinking that from that moment on I could drive by that old oak tree south of Los Alamos, the one with wide, rough scar still visible on its trunk, and not have to turn away.

And I never have, even to this day.

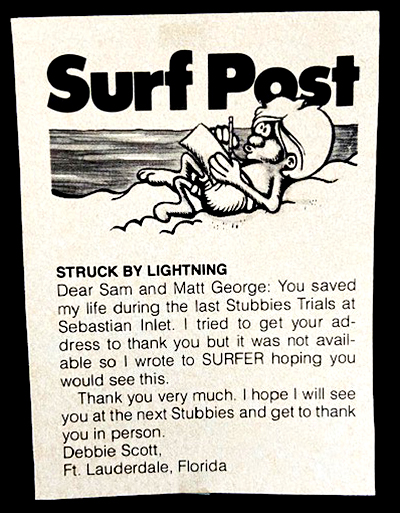

To read more of Sam's amazing true stories click on the image below.

"SURFING HEALS ALL WOUNDS!"

|

This week's Ed's corner is from May of, 2008. The surfer is none other than yours truly. Funny, I remember this day. My nephew Jesse was out with me this fun day at the Wall. Which reminds me, I'll use one of the pics of Jesse next week.

Photo by Ed O'Connell

*Click the photo above to see a larger version of Ed's Pic.

Now for Some Local and National News

The NEW UPDATE on NH2O . This is the latest article of clothing that mysteriously showed up in my driveway recently from the NH2O crew. I have to admit, I liked this custom shirt they made just for me. Check out the camera on the upper left shoulder.

The logo is very cool too. As is the name. I'm hoping they take

this to the next level. Unless this is just some strange one time promotion. Which is too bad, because I think they might sell a

few of these. The name and the logo is worth promoting.

Apparently I'm Number 1. But then again, so is everyone else who got one of these shirts. I guess "We're All Number 1!" seriously, if you guys want to get these out, I'll lend a hand. But you gotta speak up and come out of the shadows. NH2O come out come out wherever you are!

MAN SWALLOWED BY HUMPBACK WHALE

Add Cape Cod Lobsterman Michael Packard to the somewhat enviable list of those who have been swallowed by a whale. Packard has now joined the ranks of Jonah (who spent 3 days and 3 nights in the belly of a whale) and of course there's Pinocchio. Though Pinocchio was a cartoon character, but he was swallowed by a large Sperm Whale.

According to Channel 10 in Boston:

Packard was in about 45 feet of water when "I just felt this truck hit me and everything just went dark," he said. At first he thought he'd been eaten by a white shark -- the feared sharks have become fixtures off the coast of Cape Cod in the summer -- then he realized it didn't have teeth: "I said, 'Oh my god, I'm in the mouth of a whale.'"

Packard's crew mate Josiah Mayo was driving the boat and following him on his dive. "It was just a huge splash and kind of thrashing around," said Mayo. "I saw Michael kind of pop up within the mess and the whale disappeared."

Harbormaster Don German said at first he didn't believe what he was hearing when he got the call about the incident. "Honestly, we all kind of thought, 'OK, this is far fetched,' but then, when we got word from the injured gentleman, we realized it was an actual incident."

Packard had been faced with an immediate struggle in the hard, shaking mouth of the whale, as his breathing regulator came out of his mouth and he had to find it. Then, as the seconds ticked by, Packard thought, "This is how you're going to die. In the mouth of a whale." He didn't know if he would be swallowed or suffocate, he said, and he thought about his 12- and 16-year-old sons, wife, mother and family. "I just was struggling but I knew this was this massive creature, there was no way I was going to bust myself out of there," Packard recalled.

Then, suddenly, Packard saw light, felt the whale shaking its head and was thrown out of the water. "I was just laying on the surface floating and saw his tail and he went back down, and I was like, 'Oh my god, I got out of that, I survived,'" he said. Reported by Channel 10 Boston

Well, I've seen a White Shark, been chased by a Tiger Shark, and I've been charged by a Bull Moose. But I've never been swallowed by a Hump Back Whale. Not sure I want to experience that.

BRUINS LOSE TO ISLANDERS.

And that's all for the Boston Bruins this season. Hopefully they come back next year stronger and faster and Tuukka Rask is

still with them. He needs to win The Cup before he retires.

Tomorrow June 14th, 2021 is FLAG DAY.

If you have any torn, ripped, and unserviceable flags bring them to your local Veterans Post and they will

properly retire them in a very serious and somber ceremony. Yes we burn the flags.

The local Veterans and Boy Scouts hold the FLAG DAY Ceremony behind the Fire Station in Hampton (town) and properly retire them. The Public is invited. We've had years where we have burned over 5,000 flags. It's the honorable way to retire the flags that are no longer in service.

Speaking of service...Jimmy Dunn is back out there doing his duty as a Comedian making people laugh their asses off again.

KSM Photoshop of the Week

I'm reminded when KSM volunteered one year to help burn the flags with the local Scouts and Veterans. And damn, wouldn't you know the old Terrorist got a little too close to the flames and was quickly ignited with the flags of his enemy. I'm not sure who allowed this to happen, wait, yes I do. I was behind this. It's me again. Oh come on people, it's just another week of KSM and my funny photoshop skills. If you can't laugh at KSM's misery then who can you laugh at?

And so my friends, please take advantage of this weekly photo shop of the mastermind who planned 9-11 and resulted in the deaths of 3,000 innocent civilians by KSM (Khalid Sheik Mohammed).

*Note to self -must pick up a case of Lighter Fluid at

Home Depot this week.

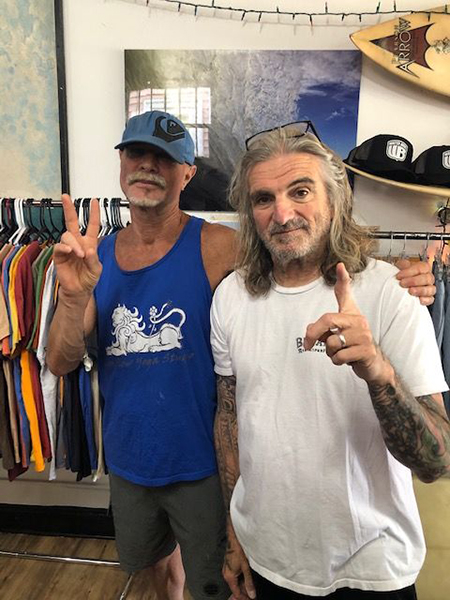

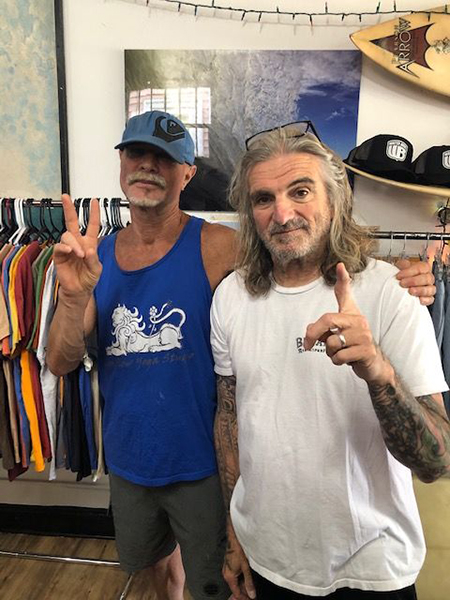

Two of my favorite 70 year old surfers. Mike Rosa and of course Sid "The Package" Abruzzi.

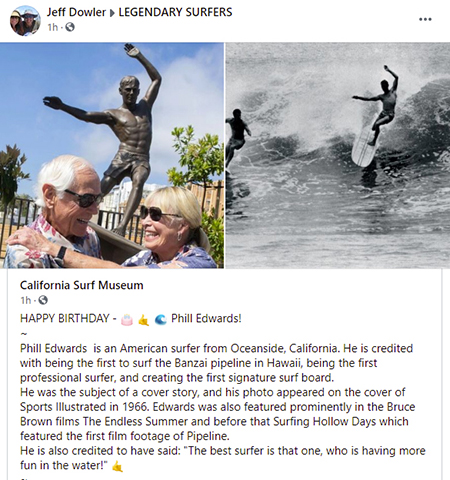

Happy Birthday Phil Edwards! One of my favorite surfers of all time. He's in my Top Five Surfers. Duke, Phil Edwards, Shaun Tomson, Tom Curren, and Kelly Slater.

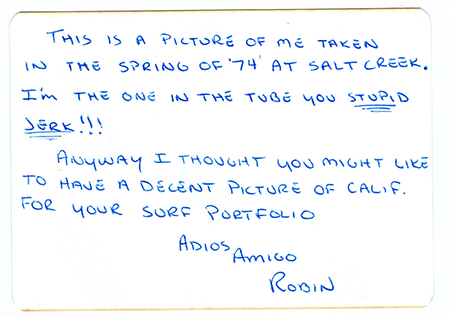

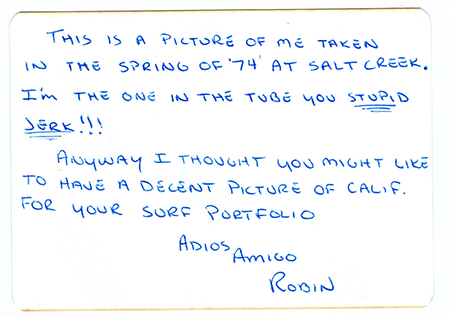

Please keep Robin Rowell in your thoughts and prayers. This is a photo and a note that Robin sent me in 1974. He's a good friend and one of the best surfers to ever surf these parts. We Love You Robin. Stay strong brother, we're all pulling for you.

REST IN PEACE John Emery 89yr old Korean war Vet

PLEASE Keep 90 yr old Chuck Dreyer (Kim Grondin's dad)

in your thoughts and prayers as he recovers from surgery.

PLEASE Keep JoEllen Bunton in your thoughts and prayers too.

PLEASE Keep longtime NH Surfer Greg Smith in your Prayers.

PLEASE Keep local Surfer/Musician Pete Kowalski in your thoughts and prayers throughout the year.

PLEASE SUPPORT THE DIPG AWARNESS TEAM!

Please

Support ALL The photographers who contribute to

Ralph's Pic Of The Week every week for the last 16 years.

** BUY a HIGH RES Photo

from any of the weeks on RPOTW.

Remember

my friends... Surfing Heals All Wounds.

Pray for Surf. Pray for Peace. Surf For Fun.

Ralph

|